Advertisement

New map of U.S. plant zones shows a warmer Massachusetts

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has released the latest version of its Plant Hardiness Zone Map — the first update since 2012. The familiar color-coded map helps gardeners, farmers and landscapers determine which plants are most likely to thrive at a given location. The zones are based on average low temperatures — a key factor in whether a certain plant is tough enough to survive the winter.

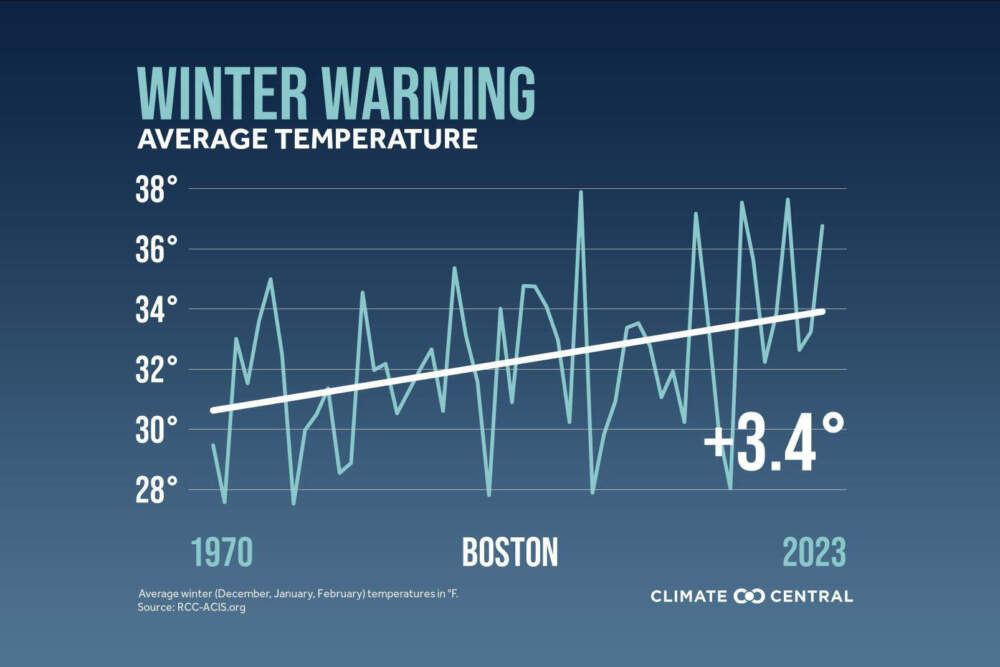

National temperature data show warmer zones shifting northward, as one might expect with a warming climate.

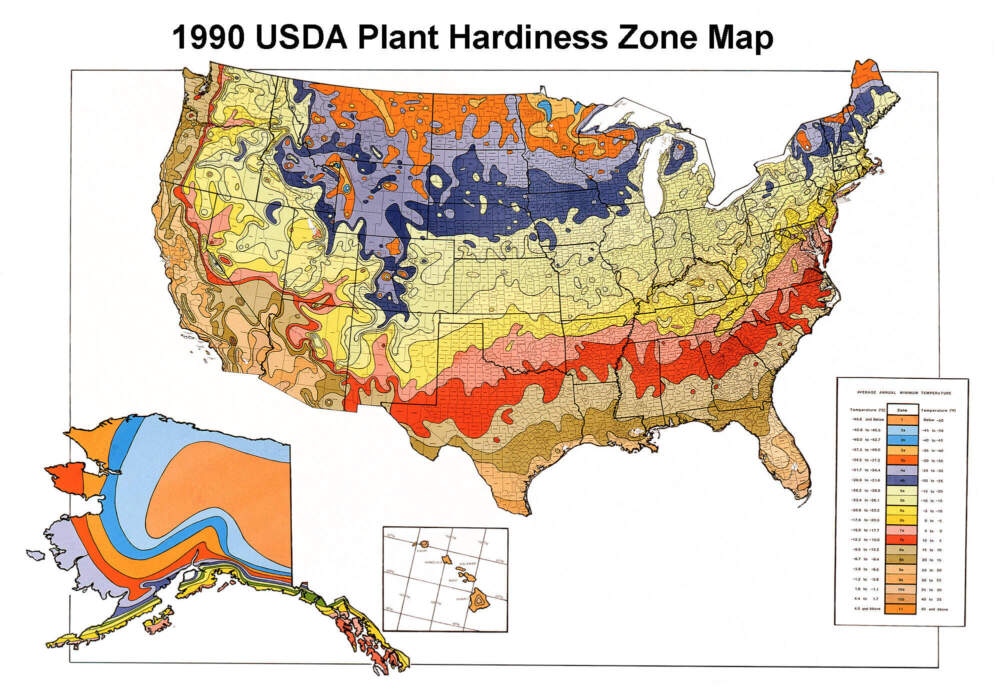

Over the years, the U.S. government created variations of the maps as researchers gathered more data, issuing new maps in 1936, 1960, 1965, 1990, 2012, and now 2023. The earlier maps were simple posters, unlike the interactive 2012 and 2023 maps. In the future they'll be updated every ten years to align with new climate “normals."

The 1990 poster was groovy, if perhaps less practical. Check out Alaska, man!

Despite the obvious warming pattern, USDA mapmakers say that the temperature updates "are not necessarily reflective of global climate change" because they are based only on average low temperatures over the last 30 years. Indicators of global climate change are usually based on trends in both high and low temperatures over longer time periods.

Here's a closer look at Massachusetts, which hasn't changed too much since the last map, though you can see a zone shift, especially in Western and Central Mass.

Most of Massachusetts now falls into zones 6 or 7, rather than the cooler zone 5B or 5A. On the one hand, this is good news for gardeners: beloved plants like figs and hydrangeas now might spend a winter more happily in greater Boston.

"It opens up a whole new plant palette," said Trevor Smith, the design and education manager at Weston Nurseries.

"However, what I worry about with people getting excited about all the new plants is that they're going to forget some of the very important plants ecologically," Smith said. Native trees and flowers that feed local bees and birds will be in jeopardy with continued warming. "I don't want people to necessarily abandon natives for all these other cool plants."

Uli Lorimer, director of horticulture at the Native Plant Trust, also found the zone shift "troubling."

Lorimer said that northern plants like Balsam fir, Red spruce and bunchberry thrive in a specific temperature range, and that range is constricting. If the plants gradually move higher up a mountain seeking cooler temperatures, "there will eventually be no more mountain to move up," he said.

Another concern: pests like hemlock woolly adelgid that are held in check by frigid winters may gain a foothold as the weather warms. Milder winters mean that more insects survive to lay eggs the following year, or even have two sessions of egg laying in one season. And warmer winters may bring even more pests, like the Southern Pine Beetle, which has already appeared in Long Island.

"I think that would be particularly devastating if it were to make its way to the Cape, which also has lots of pine trees," Lorimer said.

"One of the best things about New England is that our winters were a reset button," said Weston Nurseries' Trevor Smith. "If we continue with these warmer weather patterns, the bugs and invasive plants "won't really get knocked back, so they will begin to take hold."